Sometimes it seems like everyone is always posting about the Israel-Gaza war, but that’s not really the case. Many people haven’t posted about it at all, or maybe they only did once. The people who are being quiet could be experiencing their feelings around these events in private. Or maybe they’re trying to ignore it. I’m not going to judge any of them. I do feel a need to speak up about where I stand, as an American of Jewish descent.

My Jewish identity is pretty strong culturally, and has made itself more present spiritually as I’ve gotten older. For me, being Jewish sets me apart from other white-looking descendants of Europeans. I once told my Dad that I was thinking about visiting Romania, because that’s where our family emigrated from in the early 20th century. He said “why would you want to go there?” Later, I read more about that state’s willing acquiescence to the Third Reich, and I think I understood what he meant. Being Jewish for me has meant the absence of a connection to a specific place or homeland. I was born in America and I feel American (which comes with its own kinds of ambivalence). Any allegiance to anything apart from that would feel personally untrue.

One way in which my Judaism has informed my life is that I identify with underdogs. It was drummed into me from a young age that the Jewish people have had to be resilient and resourceful in order to endure.

In spite of that, however, my experience growing up in a liberal, upper middle class, Jewish family didn’t lend itself to conversations that would look to the Palestinians with solidarity in mind. The line in my household was always something akin to the “it’s complicated” refrain, in the rare event that the topic of Israel came up at all. (This experience feels pretty hegemonic, commonplace, typical of its era.) My parents didn’t travel to Israel after I was born and I never went on Birthright. It wasn’t until I read Joe Sacco’s book Palestine that I began to appreciate the power imbalance between Israel and Palestine, and the U.S. role in maintaining that imbalance. Over the last 15 years, I’ve come to identify Israel as having a fucked up government to say the least, and I’ve come to identify the Palestinian people as resilient and worthy of global support. I don’t appreciate that my tax dollars have gone towards maintaining Israel’s military, as the state has bulldozed Palestinian homes and fired rubber bullets at children. Certainly the Palestinians have responded with violence of their own, but the disparity between resources couldn’t be more clear. The Iron Dome speaks for itself.

I decided to re-read Sacco’s Palestine while I was on a recent tour. Midway through the book, Sacco went to visit the refugee camp of Jabalia, where he was greeted with warmth and hospitality by the deeply impoverished residents, some of whom had lived there since 1948. Their homes had been destroyed, their olive trees had been cut down, and they were scraping by while living in a squalor that was entirely imposed upon them by Israeli checkpoints, Israeli settlers, Israeli bureaucracies, and the Israeli military.

When I finished that chapter, I looked at my phone and saw that the IDF had bombed Jabalia that same day. I think it’s very possible that some of the families I read about in the book had died in the bombing.

It seems to me that the establishment of Israel may have had some good intentions, but it’s led to catastrophe. I feel a deep shame that “the Jewish state” has spent the last sixty years developing a system of oppression alongside a militaristic culture. I don’t believe in a “Jewish state” in the same way that I don’t believe in a Christian state or a Hindu state. The idea of a government selecting one group as more worthy of human rights than another is wrong morally, but simply from a realpolitik perspective, it sets the stage for reaction and pushback. The maintenance of a humiliating and violent regime of apartheid in Gaza created the conditions that would lead to a bloody and horrible response from Hamas, which in turn is being offered as justification for something the Israeli government has probably wanted to achieve for a long time: the complete destruction of Gaza, and to hell with its 2 million residents, some of the poorest people on the planet.

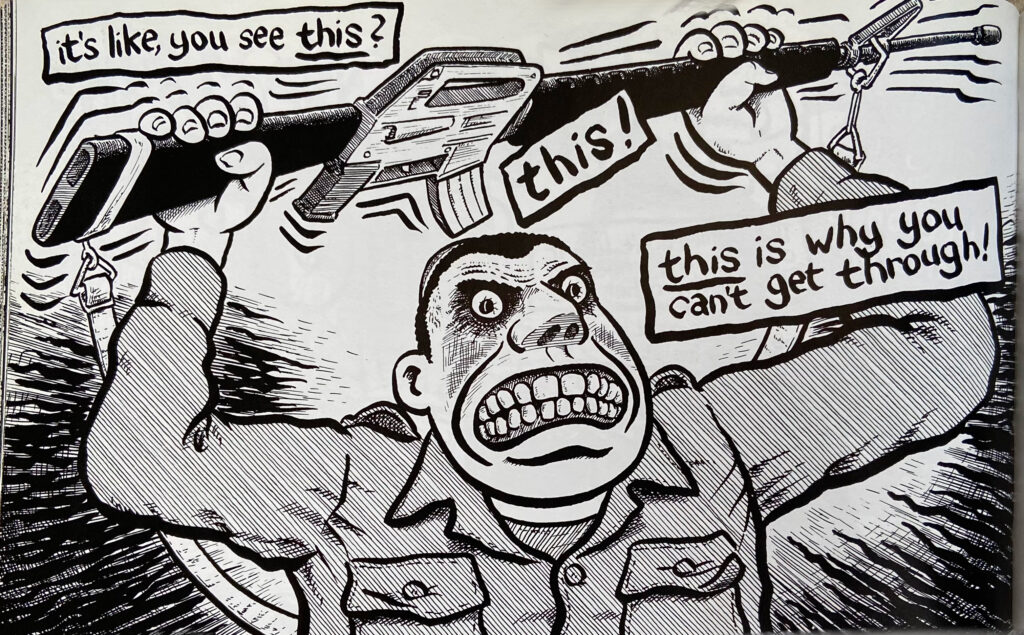

You get the sense that Israel’s policy makers resent the Gazans for simply existing, for remaining in the tiny corner of the region where Israel itself forced them to go. As Israel’s assault on Gaza with U.S. support has raged, it’s become clear that this — this! — is the modern fuel of anti-semitism. Jews collectively identifying themselves in the form of reckless and sickening state violence. Israel’s destruction of Gaza will haunt the global population of Jews for a long time. It’s disgusting from a human perspective, but if you believe anti-semitism is a problem worth fighting, it’s terribly short sighted as well.

I’m really proud of all the people who have taken to the streets to say, no, there is no justification for what’s happened over the last 40 days. (I went to one rally, I’ll probably go to more, I’ve been on the road.)

I don’t get a lot from the public discussion of aspects of my identity; it just doesn’t interest me. I’m speaking up here so I can be counted in some small way as an American Jew who looks to this nightmare and refuses to be identified with this manifestation of Judaism, the modern state of Israel.

Again, simply from a cynical political standpoint, DNC operatives must see that this has doomed Biden’s re-election, as it’s shattered his diverse voter base, who are now rightly disgusted and disillusioned. So Israel will get more of what it wants, which is a Trump presidency. What scares me is that the Israel-Gaza war will offer some sort of fucked up proof of concept in terms of what can be done to tricky pockets of resistant “others.” First apartheid, then reaction, and then a final and bloodier reaction. When I worry about the rise of global anti-semitism, I’m worried less about the seemingly eternal and ever-present hate that Jews have faced for millennia, and I’m worried more about a Jewish state behaving in a way that gives that hate meaning.

While most of the people I’ve seen speaking up about this war are calling for a ceasefire, I’m aware that I have family, friends, and collaborators who are either sympathetic to, or actively supportive of, Israel. Maybe they had a meaningful visit there, or maybe they have family there, or maybe they have spiritual reasons. When I think about Israeli people themselves, I’m reminded of a scene from the film Judgment at Nuremberg where the question is implicitly posed: are all Germans monsters? The answer is no, just as Israelis are no doubt exactly like any other group of people arbitrarily bound together by the lottery of birth. States enact monstrous policies while most people are simply trying to live their lives. Take the United States as an example.

The mess we’re in is only beginning, and everything feels equally volatile and futile. The only choice I see is to be louder and more vocal in a demand for peace, and to vigorously stand with oppressed people the world over.